Page last updated: November 17, 2021

All glass plate photographs by Harold A. Taylor. Digital images copyright © 2021 by Pinyon Publishing. No reproduction without permission.

Missions Home North to South: Dolores Santa Cruz San Juan Bautista Monterey Carmel

San Antonio de Padua San Miguel San Luis Obispo Santa Ines Santa Barbara-Glass SB-Celluloid

San Buenaventura San Fernando Rey de Espana San Gabriel Arcangel San Juan Capistrano Miscellaneous

History of the California Missions

Inception: 1770s-1830s

Without sufficient settlers to colonize a New World, Spain instead established a system to convert native peoples into subjects—Thus the conception of a string Catholic missions along the Alto California coastline beginning in 1769 with the founding of Mission San Diego de Alacá by president padre of the missions, Father Junipero Serra. Over the next 54 years, another 20 missions followed suit reaching as far north as Sonoma. But their lifespan was short, with the missions transforming away from their original intention in the 1830s. Soon after which the goal of keeping control of California (from the Russians, Americans, and British) also died when Americans found gold seized control of the territory.

Founded with only one or two padres and a few guards, the missions enlisted native Indians to live with them and help build and maintain the buildings and cultivate crops and livestock. The line between subject and slavery was thin as the padres prohibited neophytes (i.e., converted natives) from returning to their homes, essentially imprisoning them within the mission walls. In addition, many natives died of diseases brought by the Spanish missionaries. After about 65 years of mission influence, the native population crashed by an over an order of magnitude from approximately 300,000 to 20,000.

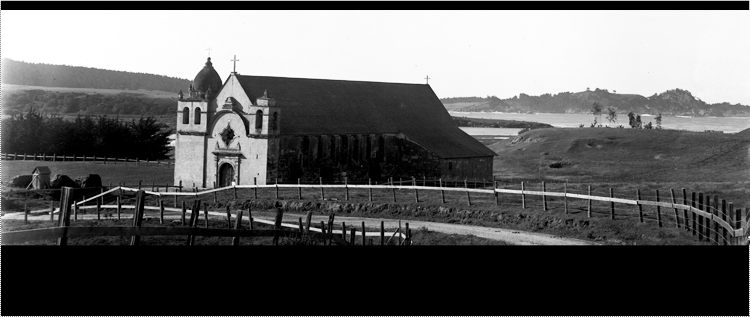

One of the first missions, Carmel, originally founded in Monterey 1770 and moved to Carmel the next year.

Earthquakes, rain, the American discovery of gold, and waning Spanish colonial power contributed to the short lifespan of the missions and they soon became relics of a brief moment in history. In 1821, Spain lost control of Mexico. In 1833, the now Mexican government controlling the missions decided to (prematurely) secularize the missions—i.e., to turn the missions over to a thriving population of newly converted Spanish-Mexican subjects. The new society was far from ready. Instead of land and buildings moving into hands of natives, it mostly ended up in the hands of wealthy non-natives.

Restoration: 1900s

Notice of the missions by artists in the early 20th century drew the attention of tourists and fueled motivation to restore the historic architecture. Early restoration often changed or masked historic elements, an effort at modernization improvements. But by the 1950s more authentic restoration proceeded.

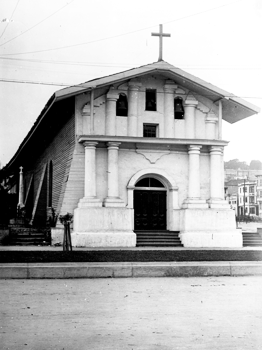

The photographs taken by Harold Taylor glimpse the missions in the window before some of the more recent restoration efforts. Through his photographs we see the missions in varying stages of life, from the weedy ruins of San Juan Capistrano to the thriving Mission Dolores on a San Francisco street before the next door Basilica was built to San Juan Bautista with a bell tower (campanario) that was only in place from 1929-1949.

Decline: Late 1800s

If the adobe mission walls did not deteriorate from rain and earthquakes, they were converted sold or rented out as stores, bars, inns, a pig farm at San Fernando, hay storage at San Juan Capistrano; and tile roofing might be dismantled for use elsewhere.

In the 1846 US-Mexico war, the missions were used as military bases. And in 1865, President Lincoln started returning some of the missions to the Catholic Church.

Abandoned Corridor, Mission San Fernando

Mission Dolores, San Francisco

ca. 1929-1949

Architecture

The missions were built with thick (four- to five-foot) walls as a way to support their own weight and heavy tile roofs. Made with sun-dried adobe (which tends to dissolve in rain) and plastered with lime stucco. Some of the more ornamental designs were inspired by similar structures in Mexico and Spain (e.g., Carmel, San Juan Capistrano, San Luis Rey, and Santa Barbara). For example, we see ornamental openings, originally introduced to Spain from the Moors. The false front feature of an “Espandaña” gave the buildings a more impressive look (e.g., San Diego, San Luis Rey, and Carmel).

San Gabriel displays a beautiful example of the campanario—a wall with openings for bells. Most missions included a corridor arcade—a shady outdoor hallway providing relief from summer heat and a place to meditate. The arcades were usually placed along an inner wall of the mission complex and contained arches supported by brick or adobe pillars.

Missions were further decorated with imitation marble (drawn in perspective), altars, niches, doors, pillars, and balconies (notable examples at Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, and San Miguel).

The “mission-style” architecture permeated the now characteristic architecture of California outside the mission walls.

Mission Santa Barbara

Mission San Gabriel Campanario Bell Tower

Sources:

https://www.history.com/topics/religion/california-missions

https://www.missionscalifornia.com/

The California Missions. Sunset Books. Editor, David E. Clark. 1979.